There have been many storied cameos in comics history: KISS, Barack Obama, Stephen Colbert, and the entire 1977 cast of Saturday Night Live. There are also plenty of instances of comic writers appearing in their own books, and a giant fabulous example of fictional characters adventuring together.

But what about comics that feature other authors? I spent some time recently looking for cameos by writers homaged in comic books and found a vampire Neil Gaiman, an alien Samuel Delany, and the mighty she-god Isaac Asimov?!? Take a look.

Neil Gaiman, Vampire Poet!

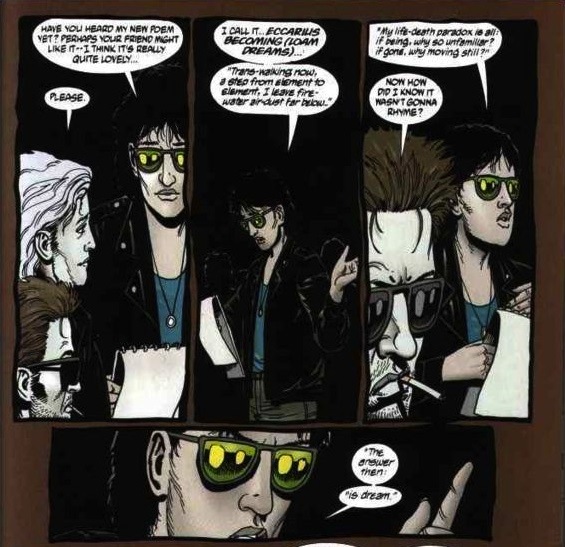

Cassidy: Blood and Whiskey is a one-shot spinoff of the delightfully profane Vertigo comic Preacher. When the titular Irish vampire travels to New Orleans, he finds a vampire cult that seems like it was designed by Anne Rice herself. He meets a fellow bloodsucker who calls himself Eccarius, and has a fake accent that matches the pretension of his name. But still worse are Eccarius’ fanboys, who fawn around begging to be “turned” and generally living up to every goth stereotype.

And then Neil Gaiman shows up. Well, technically his name is Roger, and he’s a poet, not an acclaimed fantasist, but…look at him. With his unique speech bubble font and apparent obsession with dreams, who else could that be?

Sandman is Practically a Writers’ Conference

Well, Sandman, or any random bar in Brooklyn. Heh. Since Sandman is about the Prince of Stories, it makes sense that the occasional writer pops up, but Gaiman goes far beyond name dropping, using writers and their particular neuroses to comment on the story he’s creating. Some of them, like the loathsome Richard Madoc, are fictional, but a pretty good crowd of factual writers show up over the course of the series. Mark Twain plays a minor role in Emperor Norton’s story, and Geoffrey Chaucer, Christopher Marlowe, and Ben Jonson have walk-ons. But Gaiman gives more weight to three particular icons:

When William Shakespeare first shows up in Sandman, he and his friend Christopher Marlowe are background characters in The Doll’s House, in the mini-arc “Men of Good Fortune.” We see young Will make a deal with Morpheus, proving that he has not read his friend Marlowe’s play nearly as closely as he should have. Later, we learn that the bargain was simple, on the surface: Will wrote two plays for Morpheus, and in exchange he gets to have works that will outlast his mortal life. The plays are A Midsummer Night’s Dream (of course) and The Tempest. Will actually performs the first for an audience of Fair Folk, and while it goes well, it’s also strongly implied that this costs him his son. We see Queen Titania take an interest in young Hamnet, and then we learn that he died soon after. The Tempest, meanwhile is woven into The Sandman’s final issue. Will talks with Morpheus about his life, and it becomes clear that his dedication to words has robbed him of a more direct experience of life. The issue serves as a meditation on both Morpheus’ life and Shakespeare’s, as well as (surprise!) the nature of story itself.

G.K. Chesterton, author of the Father Brown mysteries, The Man Who was Thursday, and many many pages of Catholic theology, was a particular hero to li’l Neil Gaiman. But unlike fellow-Gaiman-inspirers C.S. Lewis and J.R.R. Tolkien, Chesterton was homaged by becoming one of the few completely likeable characters in the entire run of Sandman! Fiddler’s Green is ordinarily a beautiful, rolling meadow in the Heart of the Dreaming, but when he decides to take human form, he names himself Gilbert and looks and speaks just like Chesterton. Gilbert helps Rose Walker, rescues Rose’s little brother Jed from The Corinthian, and heroically sacrifices himself to protect Dream from the Kindly Ones. Plus, in a final act of awesomeness, Gilbert refuses an offer of resurrection, saying that then “my death would have no meaning.” Gaiman made a point of giving readers flawed, often unlikeable characters, but in Gilbert he gave us a rare ray of light, a character we could trust to do the right thing, and then he used him to make a point about the use of character deaths as gimmicks.

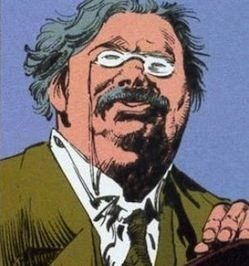

The third appearance is a little more open to interpretation. When I reviewed the second issue of Sandman: Overture I was startled by two developments: first, that Morpheus demanded an audience with the Shekinah—which is the feminine aspect of the God of the Hebrews, for those of you who haven’t dipped into the Book of Exodus in a while—and it turns out that God’s feminine aspect is the spitting image of Isaac freaking Asimov. (He’s also deliciously bitchy to Morpheus, which is fun to watch.) This raises many fascinating questions: why is Morpheus appealing to the Shekinah? Why is she suddenly an elderly male sci-fi author? Did Isaac Asimov ever travel to SFF conferences disguised as a pillar of fire? Does this mean his guide to the Bible is the correct one?

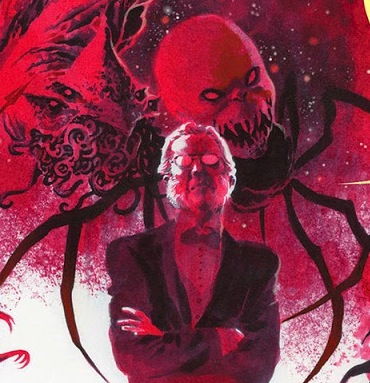

Wacky Truth Tellers in Transmetropolitan

Warren Ellis’ Spider Jerusalem is a pure distillation of the idea of Gonzo journalism, and he’s very obviously based on Hunter Thompson. But Ellis doesn’t just give us a maniacal, gun-toting HST of the future. Transmetropolitan digs into the real person underneath Spider’s bluster, and reveals the heart and dedication to truth that fuels all of his insanity, in a way that subtly critiques the way Hunter Thompson himself was turned into a cartoon by more taditional media. This alone would be great, but what’s extra fun is that apparently when Spider doesn’t shave for a while, he transforms into equally-crazy-revealer-of-divine-truth Alan Moore!

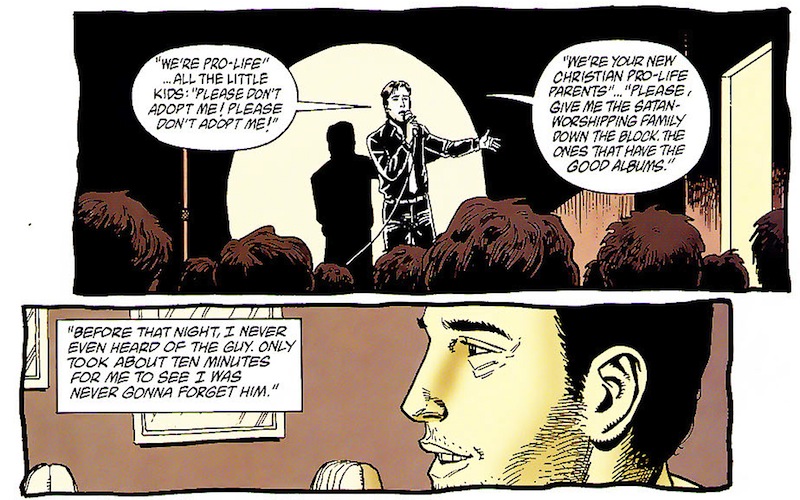

Bill Hicks Changes Jesse Custer’s Life in Preacher

My personal pick for Greatest Stand-up Comedian of All Time, Bill Hicks, appeared in Preacher. Actually, to say he appeared is in understatement: over the course of Issue 31 we learn that Jesse Custer credits Hicks with his decision to fight against his oppressive Gran’ma, and the residents of Annville. This decision leads directly to the events of the comic series. I’m including Hicks here because… well honestly because I love him, but also because Soft Skull

Press collected a bunch of his letters and stand up routines into a book called Love All the People, which is a fantastic read. So, fuck it, I say he counts as an author.

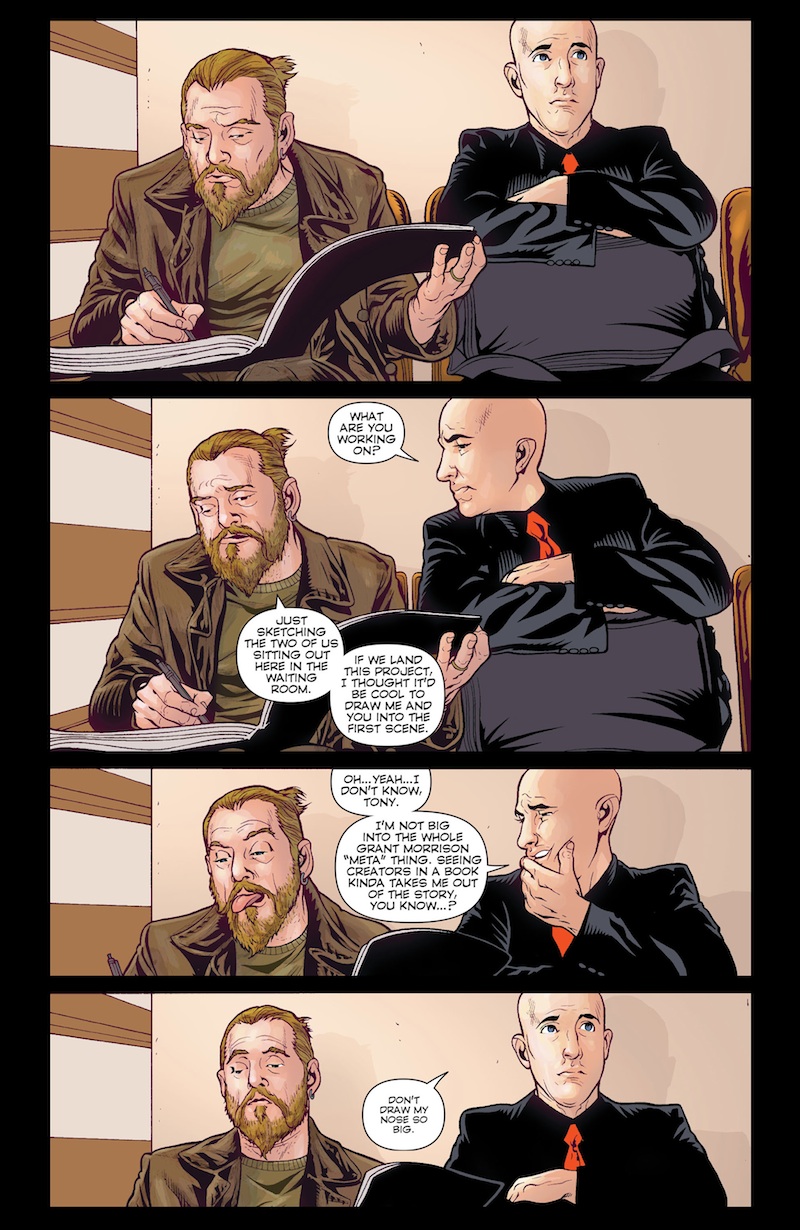

Brian K. Vaughan and Tony Harris Audition to Write Ex Machina

I’m trying to stay away from creator cameos for the most part, because I’m more interested in seeing how these comics writers have written about other writers. However. The exception to this is the mighty Brian K. Vaughan and Tony Harris, for their hilarious and touching appearance in Ex Machina.

When avid DC fan Mitchell Hundred becomes the world’s first real superbeing, it’s only natural for him to use the comics he loves as a guide to hero-ing. And once he becomes New York’s mayor, it’s also natural that he wants to be immortalized in a comic. Vaughan and Harris show up to interview for the gig, and the issue quickly turns into a meditation on life in post-9/11/01 New York…. like many BKV projects. Vaughan’s self-satire is hilarious and touching, and the ending is perfect.

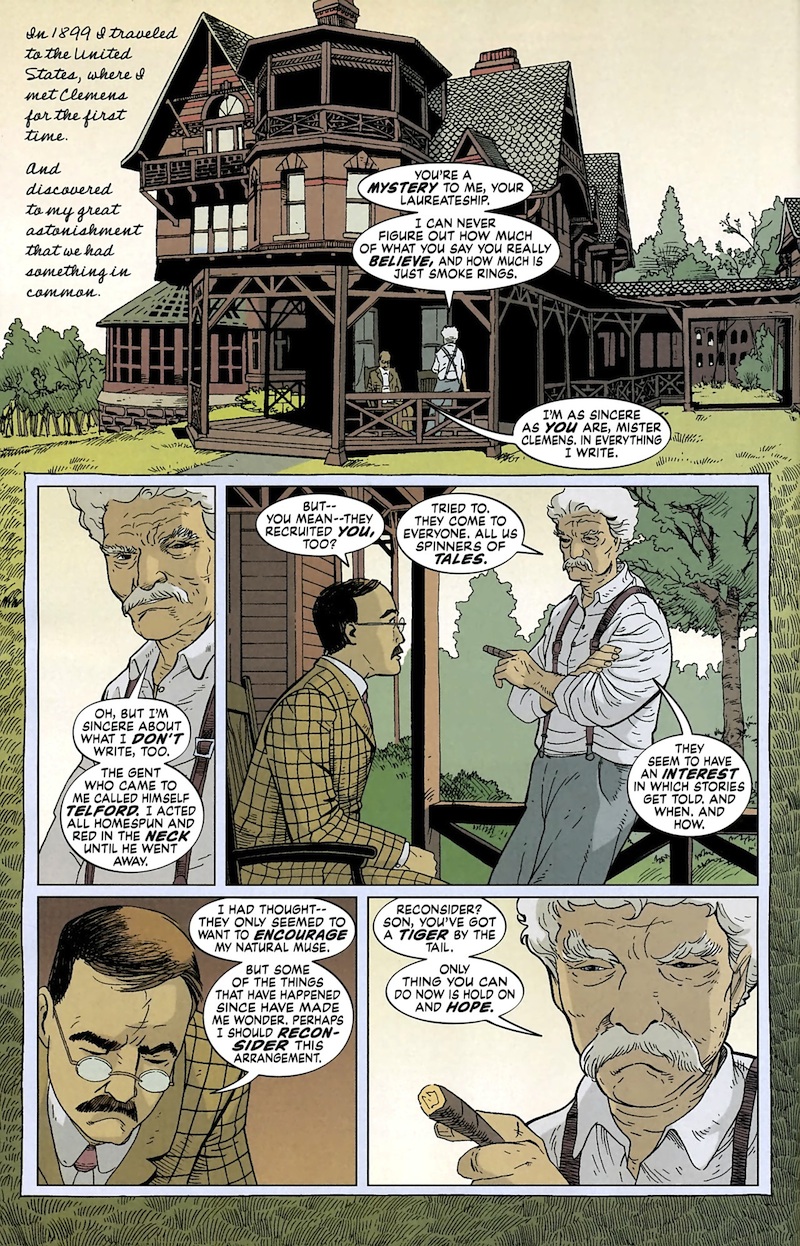

Writers Rule the World in The Unwritten

The Unwritten usually focuses on Tommy Taylor, the son of a fictional author, and the wackiness that ensues when his reality starts to melt, and elements of his father’s fiction turn out to be real. In one early issue, however, Mike Carey focuses on some real authors and their ties to the titular Unwritten, the shadowy cabal who shape reality through words. Fresh-faced Rudyard Kipling is recruited by the group and enthusiastically uses his work to promote the British Empire, not noticing all the war and cultural genocide until it’s too late.

He learns that the group also tried to recruit Samuel Clemens and probably destroyed Oscar Wilde. Carey shows Clemens as the savviest of the writers—he wisely uses folksy adages until the group decides he’s a rube—while Oscar Wilde may stay heroically snarky, but can’t save himself from prison. Kiping’s 11th hour attempts to free himself from the group speak to the idea of an author’s accountability: what does a writer (or any artist) owe to their patrons? Is there a responsibility to stay independent, even in the face of abject poverty? Is it ever worth it to sell out? And even larger: what is the artist’s responsibility to the larger world?

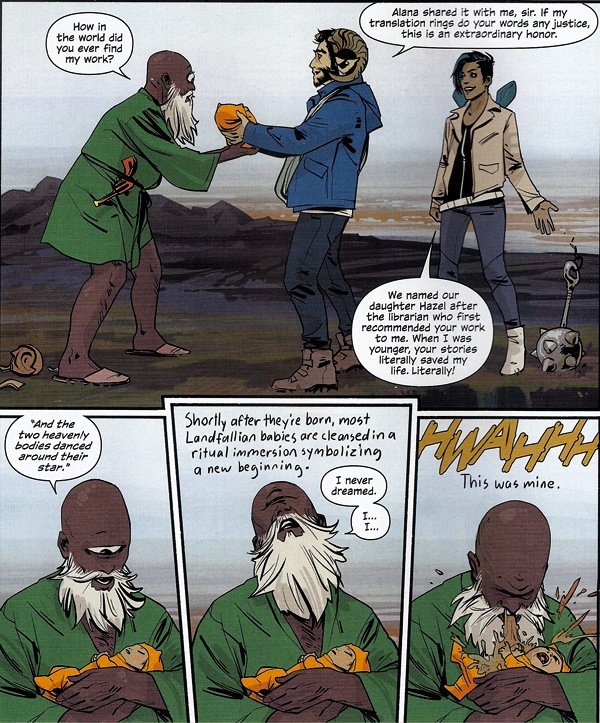

Samuel R. Delany Revolutionizes Saga

So, not only does Cyclopean author D. Oswald Heist look a lot like renowned SFF author Samuel R. Delany, he also writes books that are more than a little reminiscent of the Grand Master’s own works. A Night Time Smoke, the novel that inspires Alana and Marko to elope, looks like a trashy romance novel. However, the book actually endorses a radical pacifistic ideal, and it’s clear that, while Marko had already experienced his pacifistic epiphany, and Alana was already smitten with him, reading the book together is what sealed the deal for the two of them. When they visit Heist, they learn that this was truly his intention, but that he never dared to believe anyone would get it.

Later, when Prince Robot IV comes to question Heist, the two discuss his novel-in-progress, The Opposite of War. No, the opposite of War is not Peace, that would be too obvious. I won’t spoil the answer, but trust me when I say the real Delany would approve. Delany’s own style and philosophy permeates the universe of Vaughan and Staples’ work, and makes it all the richer.

So who have I missed? Are there any other writers lurking in the panels of your favorite comics, just waiting to spring out and talk to you about how their characters choose them, and how they really felt that the story was writing itself through them, y’know? Just be careful—they may expect you to pick up the tab.

Leah Schnelbach thinks Samuel R. Delany should cameo in every comic. Follow her on Twitter!